To boldly go between York and Selby, on the flat car-free path that follows the old railway, is to travel the entire solar system. Because you pass a 1:575,872,239 scale model of the Sun and planets, a millennium initiative of York University, getting a vivid feel for just how empty space is.

The sun is the size of a jacuzzi; the earth, about 300m away, is like a blue cherry tomato. You have to cycle 10km to get to Pluto, which – after all that – is no larger than a chickpea. And on your bike you can travel at Star-Trek warp-factor pace: the speed of light is about 1mph / 2km/h.

I’ve done the ride (the Solar System Greenway, aka Planets Trail) countless times, but have never blogged it properly, so I put that right today.

→ There’s a map at the bottom of this page.

0 Getting to the trail

From York train station you can access the trail pretty much car-free, by heading along the river and following signs for National Cycle Route 65. It’s a pleasant run alongside the Ouse and past the Millennium Bridge. If you see a scruffy old couple sitting on the bridge with tatty old bikes eating ice-cream, smile: it could be us.

The path runs right through the racecourse at Knavesmire. Watch out when there’s a meeting on. You could be in danger from incomprehending animals unused to seeing these things called ‘bicycles’ and panicking. Not the horses, obviously. The racegoers, on their third bottle of Prosecco.

1 Sun 0m

The solar system trail starts with the Sun. Turn right here and you go to Tesco; turn left and you follow the planets.

Serendipitously, after the physics department at York Uni had decided on the scale for the trail, they found that the sun model could be made with cheap industrial plumbing hemispheres that just happened to be the right size.

Astronomically, the Sun is a yellow dwarf, a very unremarkable ‘normal’ star. It’s one of around 200 billion stars in our galaxy, which in turn is one of 200 billion galaxies in the universe that we can see. We’ve no idea how much we can’t see.

The universe is evidently quite big.

2 Mercury 100m

You go under a road bridge, furnished with mounds to entertain skaters, BMX riders and cycle bloggers, the short distance to the first planet: tiny, swift Mercury.

The actual planet probably isn’t quite as colourful as the model here, which looks like a poisonous berry. Mercury whizzes around the sun in 88 days, so you’d get frequent birthdays if you lived there. You wouldn’t, however, be able to study geology, because very boringly it doesn’t have any, just a load of old craters.

3 Venus 200m

Soon after you get to Venus, a nightmare place of furnace temperatures and an atmosphere of sulphuric acid: a stark lesson about what happens to planets that once had runaway global warming. Thank goodness that couldn’t happen on earth, thanks to rigorous domestic policies cutting down fossil fuel use, and strong international co-operation by responsible governments. Oh.

The model here is a clean, attractive white, looking like a small ping-pong ball. Ah, how innocent and friendly. Appearances can be deceptive. I know some people like that.

4 Earth 300m

A few yards further on is our home, the perfect planet for life. Or at least it was until we came along. It’s actually more of a double-planet system – the Moon is pretty big in relation to Earth, compared to other planets’ satellites – and the model here illustrates that, with a pea-sized Moon nestling close to the Lindt-chocolate-sized Earth.

The paint’s peeling off of the Earth, so bits of the carefully-depicted continents and landmasses have flaked off. It’s decomposing before our eyes. Oh.

5 Mars 450m

The Red Planet of Mars comes shortly after, and again, only some of the paint is left, giving the misleading appearance of scarlet continents floating in a black sea. We’ve sent rovers to land on and explore the Martian surface, and they’ve sent back astounding images of its coppery, sandy, rocky surface: you get an idea of just how astonishing this achievement is when you see how titchy the Earth is and how far away.

From here – the limit of the relatively crowded inner planets, jostling with each other – things get sparser. You cycle through a housing estate in Bishopthorpe, blissfully unaware of the asteroids that would be threatening high-impact strikes on your surface, and pass the cafe-garden-centre place of the Brunswick Cafe.

It’s hard to think that this used to be East Coast Main Line, the very track hurtled along by Mallard, the old fast way between London and Edinburgh. It closed in the 1980s: nothing to do with Beeching, and everything to do with potential mining subsidence. (Trains now go a few miles to the west.)

6 Jupiter 1.4km

After a longish stretch past houses, you arrive at the beach-ball-sized multicoloured globe of Jupiter. Recently (a few weeks ago, apparently) the planet was joined by a Portrait Bench, one of those pathside Sustrans projects where local heroes are portrayed in metal silhouette by a place to sit and ponder their legacy. We have Dave Jackson, a stalwart maintainer and champion of the cycle path, and actress Dame Judi Dench, who comes from York. I think Ms Dench is at 1:1 scale.

In Holst’s orchestral suite, Jupiter was the Bringer of Jollity, but it’s not a very jovial place. It’s a gas giant with no solid surface, zillions of moons, and unconscionably violent storms that have been raging for thousands of years, such as the Great Red Spot.

7 Saturn 2.5km

It’s a kilometre or two to the celebrated ringed planet of Saturn, and you cross a celebrated bridge en route (2.2km). Sitting on top of it is a wire sculpture of a character who looks rather like the cartoon character Dilbert, fishing in the Ouse below. He’s caught a train – oh, very good – and a dog behind him is cocking its leg on his casually grounded bicycle. A salutary lesson in what happens when you don’t have good bike parking.

Saturn is there in its haloed splendour, like a cosmic sombrero. It has some curious moons with sub-surface oceans and geological thermal energy, and a faint possibility of very primitive life lurking in their depths. Insert your own joke here about Tory cabinet ministers/ Audi drivers/ daytime TV etc. Saturn would float if you had a big enough bath to put it in: despite its status, it’s actually a lightweight. Insert your own joke here about Tory cabinet ministers etc.

Just beyond Saturn is a model of the Cassini-Huygens probe that flew to the planet and examined it while in orbit in the 2000s. There’s also an honesty hut with coffee and snacks, and a place to sit and ponder the meaning of life.

8 Uranus 5.1km

The planets are thinning out now, and it’s a few kilometres along the now straight-straight-straight-flat tarmac path to Uranus. Bill Herschel discovered it in his back garden in Bath in 1781 (I used to live next door but two); at first he wanted to call it George, before settling on a completely dignified alternative with no lowest-common-denominator comic possibilities at all.

Uranus, like Saturn, has rings, though they’re much fainter and weren’t discovered until 1977. They’re here on the model, which is one of the trail’s most striking. Its poles are bonkers, pointing sideways instead of up, perhaps the result of some whopping great collision or close-pass in epochs gone by.

9 Neptune 7.9km

Distances feel pretty stretched-out now, as you roll along the smooth, samey, tree-lined path. Under a road bridge there’s a small tribute to Yorkshire’s great cyclist Beryl Burton, whose day consisted of working on a rhubarb farm, going home to make the family tea, and then going out racing and setting world records even men didn’t match.

The ‘ice giant’ of Neptune, discovered in 1846 exactly where science predicted it would be, comes almost as a surprise – easy to miss when you’re cycling in the zone – but once seen, its bright shiny blue ball model here is not forgotten. Like Uranus, the real Neptune has faint rings, and like Jupiter it has a stormy Great Spot or two.

10 Pluto 10.3km

Of course, strictly speaking, Pluto isn’t a planet any more. It was demoted in 2006 to status of dwarf planet by the spoilsport International Astronomical Union because they say it’s just too small and rubbish to be taken seriously. But as far as York is concerned, Pluto is still a planet, because here it is on the Planets Trail, just outside Riccall, and about 10km from the sun.

Pluto’s even more of a double-planet than the Earth, thanks to its ‘moon’ (or rather, partner-planet) Charon. This is pronounced ‘Share-un’, ‘Care-un’, or ‘Chair-un’, depending on who you ask. Maybe try asking someone called Sharon. Anyway, the two partners are here on the model in all their tininess, sitting next to each other on pillars like a salt and pepper set.

Just before Pluto is a new artwork, installed this year, based on an old railway signal. It sets an at-a-glance model of the planets on a solar-system-size bike wheel, with a hip light green fixie bike of unimaginable size in comparison. To say nothing of the dog.

Just beyond Pluto is a one-third-scale model of Voyager 1, a space probe launched in 1977 into the far reaches of the solar system. It sent back pictures and data as it passed the planets and is now far beyond Pluto in deep space. It carries a record made of gold in case aliens with a 1970s hi-fi system find it one day, so they can hear what our music sounds like. It also carries maps for them to find us in case they want to invade. Though by the time they arrive in the far future there will be no human beings left and the Earth will long have been a wasteland. In a century, say.

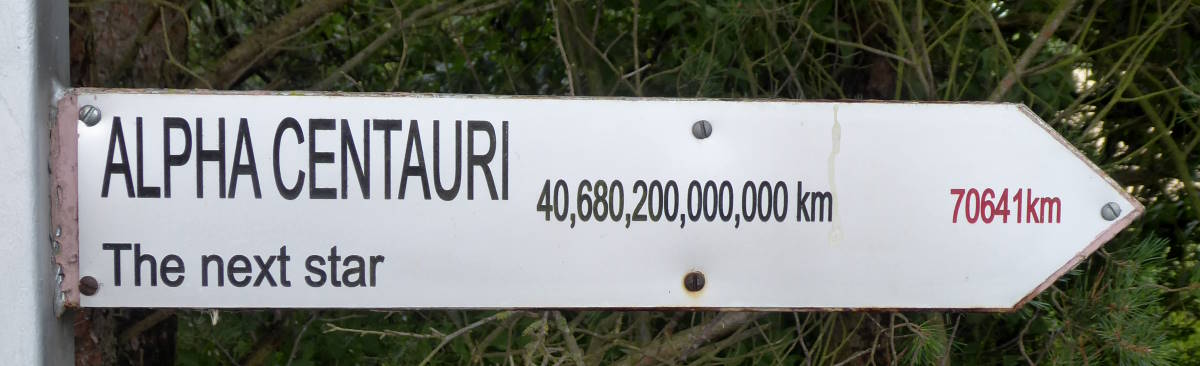

Even at our 1mph-speed-of-light scale, it’s a blooming long way to the nearest star. Proxima Centauri would be over 70,000km away, or nearly two laps of the entire Earth. And P Centauri is just another one of 200 billion stars in our galaxy, 200 billion galaxies…

Now you can continue along NCN65 (via some quiet roads and humdrum roadside paths) about 6km to Selby, where you can admire the Abbey, find refreshment, and get a train back to York; or you can turn round and retrace your steps.

MAP

To see where the planet models are, select ‘[Google] Map’ from the drop-down on top right of the map below, and zoom in.

OTHER SOLAR SYSTEM MODELS

One solar system model not enough for you? York has another, sprawled across the university campus, with a walkable scale and oversized planets in bright colours that students occasionally steal. There are also others around the country, notably along the Taunton–Bridgwater Canal. I’ve also ridden past one in Kent, and even in Copenhagen. But York’s Solar System is the best.

For another guide to the Solar System trail, see the excellent Hedgehog Cycling website.