Pontefract is Liquorice Town. Or was, anyway. The friendly, lively West Yorkshire place, its name corrupted by sweet-chewers, gave the world ‘pomfret cakes’ – chewy aromatic liquorice pastilles, stamped with an image of its historic castle.

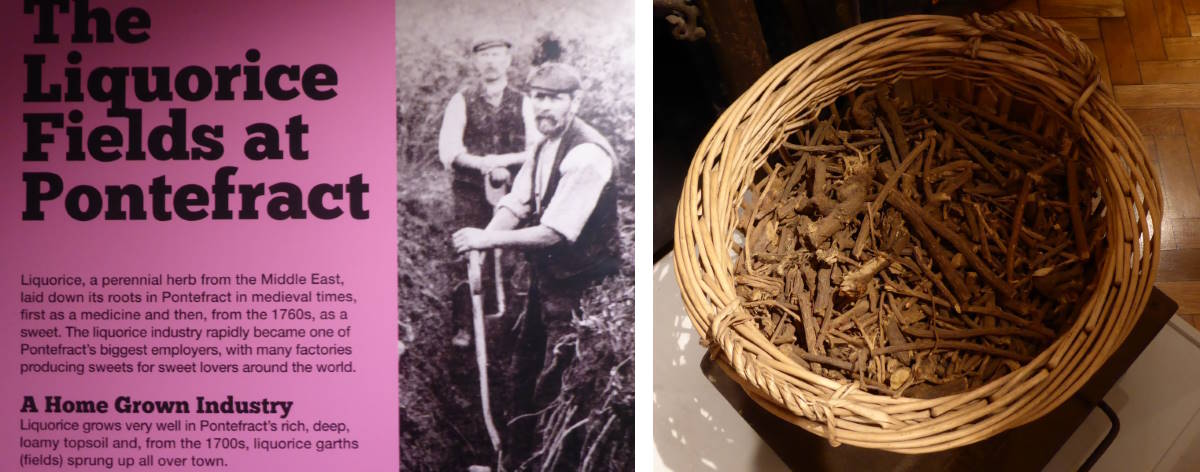

Liquorice was big business here through the 1800s and early 1900s, with ten factories employing over 5,000 locals. They turned liquorice roots, locally grown in the deep topsoil ‘garths’, into goodies that fed the world.

That all declined thanks to globalisation and changing tastes, though. For many decades tastier, cheaper liquorice has come from places like Turkey or Iran, and – following the rise of chocolate as the world’s preferred confectionery post-WWII – the root extract is more likely to end up flavouring American cigarettes than sweeties.

But ‘Ponty’ is still very much liquorice flavoured, even if there’s only the big Haribo factory left. I started my gentle exploration by bike at the castle, just two minutes’ ride up from Pontefract Baghill station.

(Baghill is one of Ponty’s three stations, all of them unstaffed, and possibly the shabbiest and most forlorn: it has the air of one of those closed-down restaurants that soon mysteriously burns down, to the advantage of some shady developers.)

There’s not much left of the castle now – it was demolished after the Civil War – but it used to be a key strategic hold for anyone wanting to control the North. But its remains make a fine and bracing stroll, with a helpful little visitor centre, a cafe, and a herb garden with some real live growing liquorice bushes.

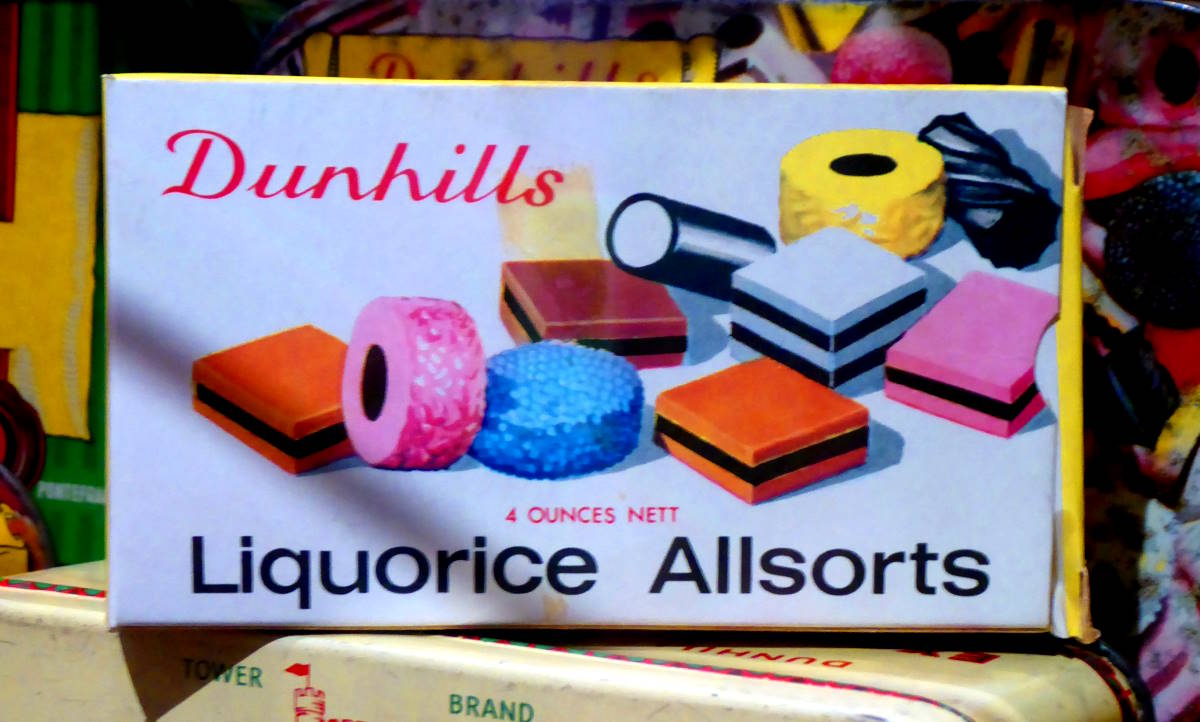

It’s here, in the castle grounds, that the Liquorice Boom started thudding, back in the 1700s. The medicinal benefits of liquorice roots – a member of the bean family – had been known since ancient times, but in 1760 Pontefract chemist George Dunhill found that adding sugar made it a rather tasty sweet.

So the oft-told story goes. Dunhill was only seven at the time, though, so perhaps we should take the story with a pinch of salt as well as sugar.

Still, that kick-started the whole global sweet-liquorice thing, and for many decades Ponty’s economy thrived, before that postwar slump.

There’s still the Haribo factory, though, churning out bags of stuff to the delight of kids, the relief of parents, and the dismay of dentists everywhere. In its outlet on Front St I picked up a bag of pomfret cakes, fresh from the laboratory next door. Like Guinness in Dublin, maybe.

Ponty’s town centre is much pedestrianised, and quite pleasant to stroll or ride round. (Coming from York, I was disoriented to see a Micklegate and Gillygate.) There’s a nice little covered market hall with lots of cheap cafes, a trad sweetshop where you can buy pomfret cakes by the ounce (so I did) and a super beer stall, the House of Ales.

The proprietor, Karl, has brewed liquorice-flavour beer in the past (notably for Ponty’s annual Liquorice Festival in July) and told me he may start again if there’s enough demand.

The town museum – just behind the library/‘tourist info’, where the enthusiastic staff gave me good local intelligence – is well worth a visit if you’re interested in root-related stuff. There’s a section on liquorice, with a cabinet containing almost a hundred confectionery boxes, and a soft-play area with cushions shaped like liquorice allsorts (which are actually a Sheffield invention, but we’ll pass over that).

Here I learned of liquorice’s role in classic films, chewed as stage props by Charlie Chaplin (‘a shoe’ in The Gold Rush) and Richard ‘Jaws’ Kiel (a ‘cable car cable’ in Moonraker).

I wandered up Liquorice Way, which has a blue plaque commemorating the town’s crop history. Right on it is the Counting House, Ponty’s oldest building, being refurbished as a pub. I look forward to liquorice-flavoured classics appearing on its bistro menu, along with liqueurs and ales.

A mile or two west of the town is Farmer Copley’s, perhaps the only place seriously growing liquorice in Britain today. It’s the sort of vibrant, 21st-century, diversified-business farm that features on Countryfile: restaurant, cafe, farm shop, cosy events spaces and more.

I chatted to owner Heather Copley, who told me about their labour of love growing liquorice: it takes seven years to get the crop up to marketable quality. Last year the hot weather caused it to flower unhelpfully, but next year (2024) there should be enough to sell in the farm shop. It’s a novelty rather than moneymaking exercise, but clearly Heather is keen to keep Pontefract’s liquorice tradition alive.

While in the shop I also picked up a bottle of Great Newsome Brewery’s Liquorice Lads Stout, produced in collaboration with Copley’s. I’ll look forward to enjoying that at Christmas, with my locally-sourced venison. (By which I mean our local Lidl.)

Back in Pontefract I couldn’t resist a non-liquorice-related circuit of the racecourse. Yorkshire has nine racecourses (Beverley, Catterick, Doncaster, Pontefract, Redcar, Ripon, Thirsk, Wetherby, York) and two of them – York and Pontefract – have perimeter tracks, enabling you to ride the complete circuit of the course. The one in Ponty is big: about two miles round.

(Yorkshire also boasts the unconventional ‘racecourse’ of Kiplingcotes, which I’ve cycled before.)

The name ‘Pontefract’ has a curious origin, stemming from the Latin for ‘broken bridge’ – supposedly after a roadworks of historic significance nearly ten centuries ago.

The location of said crossing isn’t known, but was probably not far from Ferrybridge a couple of miles northwest of Ponty, where a historic bridge and modern main road jump over the Aire, giving fine views of a disused power station. I cycled there a couple of years back, so wasn’t bothered about doing it again.

But I still had three hours before my train back to York (direct, but very infrequent services). So I spent the first half of it wisely in the library, reading Liquorice by Briony Hudson and Richard van Riel, a lively, fascinating and colourful romp through the root’s history and cultural impact.

Then I spent the second half less wisely in the Broken Bridge, the Wetherspoon round the corner.