Britain’s favourite 20th-century poet (whose centenary is in 2022) wasn’t initially impressed by Hull. Nice and flat for cycling, was Philip Larkin’s faint-praise damn. But he lived, worked and (early on, at least) rode his bike here for thirty years until his death in 1985. The city inspired his best work.

And it’s work which cyclists can especially appreciate thanks to the Larkin Trail, best done on two wheels. Its series of plaques in and around the centre (plus excellent guide PDF) highlight the places significant in his life and words. Many of which, agreeably, were pubs.

Anyway, I followed it today, and – though I grew up in a village just outside Hull – it took me to many places I hadn’t explored before. Many of which, agreeably, weren’t pubs.

The trail has 25 plaques in all, but nos. 20 to 25 are spread around East Yorkshire, meant for individual visits rather than a linear journey. So I was doing the 19 in the city, in order, on a mild grey day between Christmas and New Year. This was how things went…

1 & 2: Royal Hotel

Plaque 1 is inside the lobby, by a small display of photos. The hotel was closed because of Covid on my visit – however, Hull people are generally a down-to-earth, inclusive, we’re-all-in-this-together lot. The cheery security staff were happy to let me in to have a quick nose around, and keep an eye on my bike outside meanwhile. If anyone tries to nick it, I said, tell them not to take less than £200 on Gumtree.

Plaque 2 is outside (on the side of the pillar with that red barrier before it). It celebrates a Larkin verse set here, describing the silence laid like carpet, and the salesmen who leave full ashtrays before getting the train back to Leeds.

Different now of course. There would be no smoking, you’d have Abba in the background, and it’d be a replacement bus because of signalling problems at Micklefield.

3: Paragon Station

Plaque 3 is near a splendid statue of Larkin. It’s late May 1955 and he’s dashing off to get the London train that he immortalised in The Whitsun Weddings. It’s perhaps his best known verse (if you discount the one about your parents tucking you up) and one of the nation’s favourites.

The opening words are there, beneath his feet; at the other end of the journey, inside Kings Cross, a companion stone carries the concluding lines.

Larkin never married himself, of course. He didn’t much like going to London, either.

4: City Hall

Hull was among Britain’s most bombed cities in WWII. Among the few surviving buildings was the splendid City Hall and environs; Plaque 4 is supposed to be here but seems to be missing.

However, nearby are the remains of Beverley Gate, the old city walls. Here in 1642 Hull’s famously independent-minded citizens slammed the door in King Charles’s face, before presumably telling him to sod off back to London.

If the Queen turned up today in similar circumstances, I would do things rather differently, given my views of royalty, tradition and hereditary privilege. I’d repossess the property and wealth that they’ve embezzled from the people, strip them all of their titles, and only then slam the door in their face and tell them to sod off back to London.

5: M&S, Whitefriargate

Hull’s post-fishing and post-industrial economy struggles, like many places. The once booming shopping axis of Whitefriargate is now a forlorn sequence of shutters, charity shops, council-supported enterprises and head-above-water retail. Marks and Spencer, elevated in a Larkin poem about the shoppers in a cut-price department store, closed in 2019, though Plaque 5 is still there.

What will become of the building? A Wetherspoons, maybe? There’s a Spoons about two hundred yards away, so that’s probably far enough to merit another one.

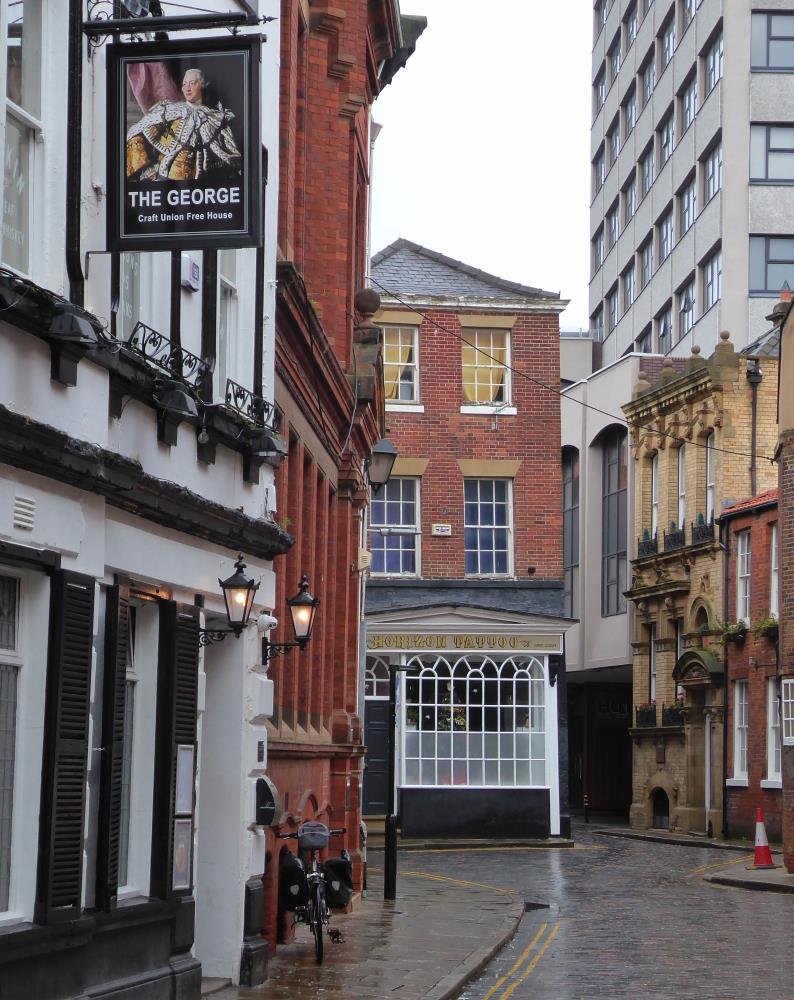

6: Land of Green Ginger

Hull’s most curiously named street is the site of Plaque 6. Nobody knows the origin, though it would make a good children’s book title, perhaps for a tale involving a magic window.

Because the unremarkable cobbled lane is the site of England’s smallest window – no, I didn’t realise this was a thing, either. It’s a vertical slit about the size of a bootlace, and is marked with a brass plate. Just for the record, it’s not double-glazed, nor is it tilt-and-turn.

Just round the corner is an alley leading to the surprise of a secluded pub with beer garden, a Larkin haunt. Ye Olde White Harte is a superbly atmospheric pub from 1550 where the plans for Britain’s Civil War were hatched in 1642: here the decision to freeze out Charles I was made.

Sit amid the dark wood panels, ancient inglenook fireplace and barrage of well-kept cask ales such as Ossett Blonde, and you can channel that wonderful spirit of making radical plans for a better world which don’t quite work out as you’d hoped.

7: Trinity Square

Hull’s grand but curiously obscure central church, built in 1285, was made a Minster in 2019. See? You just have to be patient sometimes.

Plaque 7 is here, celebrating the city’s strong poetic tradition (one which surprises many). It’s behind a statue of 1600s Hull poet Andrew Marvell, on the wall of Kall Kwik printers, both of which seem appropriate.

Just off the square is the main central market – a place of interesting niche shops and enticing street food stalls, though it was mostly closed on the day I was there. It’s also the site of a rare K1 phone box, one of the original wooden models from the early 1920s.

They’ve taken the phone itself out now, of course. Just as well. Some of my mum’s more talkative relatives might still be nattering in there.

Part of the Market is Bob Carver’s fish and chip shop, which claims to be the home of one of Hull’s great culinary contributions to the world: the ‘pattie’, a fried potato cake. Pattie and chips was a popular meal of my childhood. Yes: fried potato accompanied by fried potato.

Don’t worry, there are healthier options on offer too. Fried Mars bar, for instance (£1).

8: Victoria Pier

I rode the new ped- and bike-bridge which crosses the dual carriageway to link the city centre with the historic, and gentrifying, marina area. Here are upmarket galleries and bistros, and a lot of boats.

Plaque 8 should be here, but I could find no sign of it. And the Pier itself was fenced off and out of bounds.

Once, this riverfront was famous as one of Britain’s rare railway stations without any trains. It was the booking office for the ferry across to Lincolnshire, much frequented by Larkin, but rendered obsolete by the opening of the Humber Bridge in 1981. There’s nothing to see of that now.

The public toilets are still there, unchanged from when they were built in 1926. They feature in Lonely Planet’s 2019 list of top things to see, right up at No. 483. However, the lush, greenhouse-like, carefully maintained internal additions have gone; it’s just an unremarkable period bog now.

The woody old Minerva pub nearby, with its quirky minuscule snugs, is worth a look, at least. Larkin must have enjoyed a drink or two in these, particularly as there wouldn’t be room in them for anyone to join him.

There’s also the stirring view of The Deep, Hull’s mighty world-class aquarium, with its sharklike profile, and another quirky phone box: a rainbow-coloured one in honour of Hull Pride.

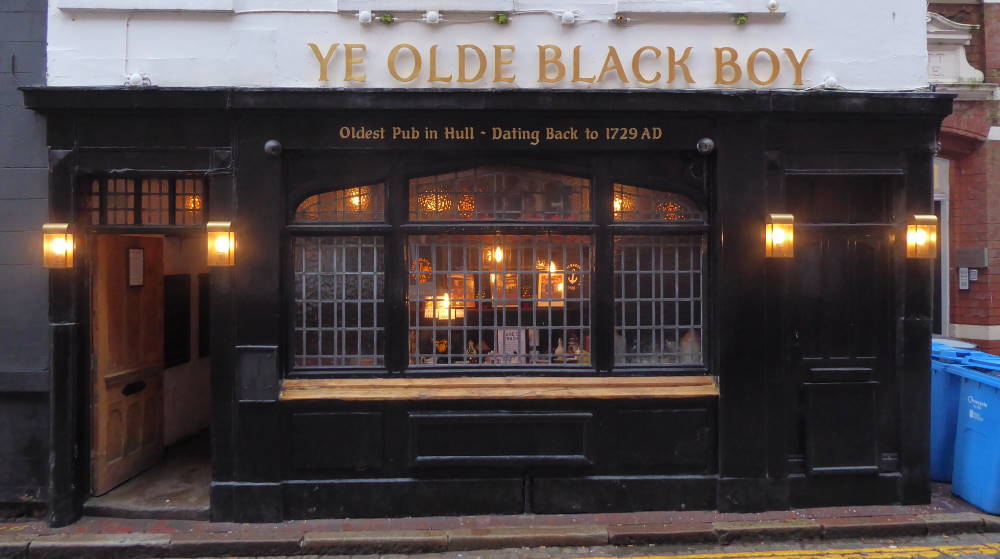

9: Ye Olde Black Boy

Jazz buff Larkin gave talks on the subject in this woody 18th-century inn, no doubt to the accompaniment of a few pints of Worthington E, or perhaps Ebm7b5. Hull doesn’t have much of an Old Town, but it’s pleasant enough to cycle through.

And there are some good museums, all free. Wilberforce House, well-preserved home of the anti-slavery campaigner, is well worth an hour; while the adjacent transport and shop museum Streetlife has a floor full of vintage bikes.

However, both the House, and the bike floor, were closed on my visit. The Black Boy wasn’t, happily. Plaque 9 is supposed to be on one of its external walls, but neither I nor the staff could find any trace of it. Oh, no! But why?… which are, incidentally, the titles of two compositions by American clarinettist Pee Wee Russell, one of Larkin’s favourite jazzers.

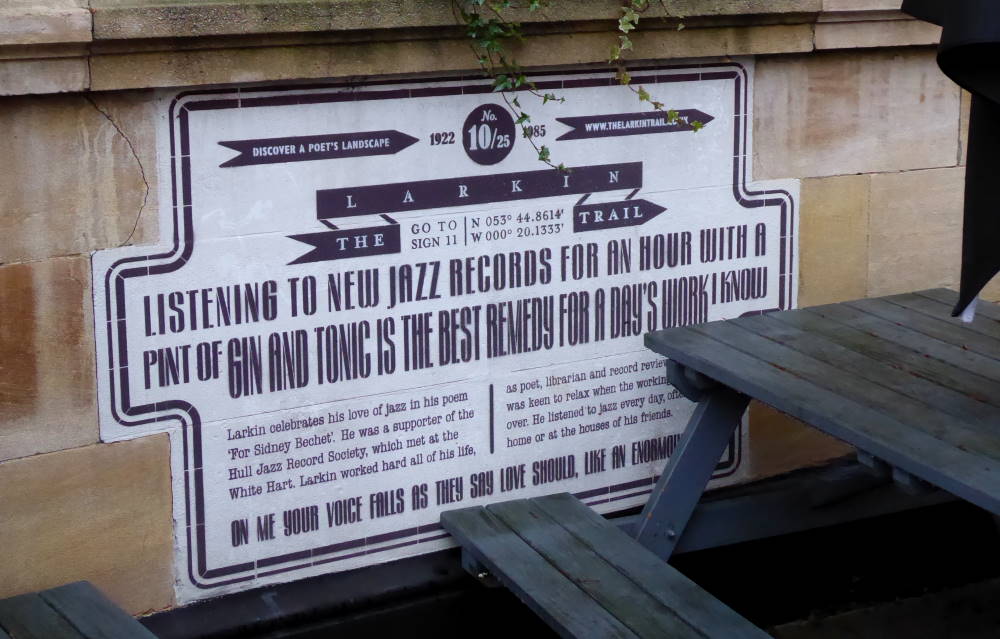

10: The White Hart

Not to be confused with the Olde White Harte, this is yet another of Larkin’s go-to (and not-leave) pubs, important for its unaltered 1904 interiors. The beer garden at the side contains Plaque 10.

11: History Centre

Serious scholars wishing to learn more about Larkin, rather than just sitting around in his favourite pubs, can visit this place and consult its extensive collection of documents, personal papers and books related to the poet.

I’m obviously not a serious scholar. Anyway, Plaque 11 is here.

12: Hull Royal Infirmary

Larkin’s memorable poem about the slablike hospital building, celebrated in Plaque 12, was written before he became a regular patient here.

Not mentioned in any Larkin Trail info is a recently installed display in the Ophthalmology Dept, inside the hospital.

It features three of his pairs of spectacles, with his prescription: I was amused to see his sight was quite as bad as mine. There is also the text to an unpublished poem of his, Long sight in age.

It’s a couple of minutes’ ride from the train station, and en route I passed an end-terrace mural celebrating the Headscarf Heroes, a group of 1960s campaigners for safer conditions on their menfolk’s trawlers.

Having to run home and family for weeks on end while their husbands were away fishing created a tough breed of women characteristic of Hull, and particularly the Hessle Road area. My mum is from Hessle Road.

If anyone in Westminster had thought the lasses down from Hull might be easily fobbed off and sent back with empty platitudes, they’d soon have been put right by Lil Bilocca and co.

13: Spring Bank Cemetery

I’d been here before but forgotten just how weird it is. Once the grand burial place for the city’s 19th-century great and good, most of the cemetery is now overgrown and dilapidated: grand obelisks and towering headstones loom through a jungle-like wilderness.

It’s gloomy, dark, unsettling and strange, and most normal people want to get out of the place as soon as possible. So of course Larkin loved it, as Plaque 13 at the entrance notes.

It’s just over the road from my secondary school, Hymers, which I also found gloomy, dark, unsettling and strange, and wanted to get out of the place as soon as possible. I’m sure it’s all much nicer now.

14: Pearson Park

Larkin’s longtime home was a rented flat opposite this pleasant park – where you can find Plaque 14 – and some of his poems (such as Toads Revisited) reference the places.

The house itself is a bit shabby and overgrown now, but the park was trim and gently sociable with families strolling round the ponds, bandstand and fountains.

I like fountains because when they’re working, they’re actually playing. And when they’re playing, they’re actually working. Like being a cycling writer.

15: Westbourne NHS Centre

Philip Larkin died here on 2 Dec 1985.

Death stalked a lot of his poetry, perhaps most chillingly in Aubade. Part of it is inscribed on Plaque 15 on the hospital wall: I am going to the inevitable… Not to be here, not to be anywhere, and soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true.

Gulp. It was all rather sobering. Carpe diem. Time to get riding again.

16: Newland Ave

Plaque 16 is just off Newland Ave, a lively studenty area with some enticing and ethnic places to eat.

(I had a jungle curry at a Thai place, and picked up a can of lager for later on from a polski sklep, making the lass behind the counter smile with my Polish.)

Larkin did his shopping here, and is now also commemorated by Larkin’s Bar, a quite excellent community place with cask ale for £3.30.

I suspect he’d have been more interested in this information than the price of cucumbers, the subject matter of the plaque.

I don’t know what he’d have thought of the bike parking, though.

17: Newland Park

The only home Larkin ever owned was 105 Newland Park, near the university library where he worked.

In contrast to his Pearson Park flat, this is well-kept and trim, and its balcony even sports a large plastic toad statue painted to imitate Larkin’s bookish appearance: ‘the toad’ was his way of referring to the tedious necessity for work. Being a cycling writer I wouldn’t know much about that.

Plaque 17 is a few hundred yards away from the house, up the end of the road.

18: Hull University Library

Larkin’s day job for thirty years was running the library here, and the combination of administrative routine, academic ambience and downtime-enabling security suited him.

I was amused by the fact that the counter staff were totally oblivious of him and his work. Eventually I found Plaque 18, by the side entrance.

19: Cottingham

Three or four miles outside Hull is Cottingham, styled as the ‘biggest village in Britain’, but feeling more like a small, smiley market town. Despite growing up a handful of miles away I’d never really looked round Cottingham’s centre.

It’s rather pleasant, with indie shops and the welcoming pub of the Duke of Cumberland, site of Plaque 19. (There’s also a Larkin display on a wall inside.)

Larkin was buried in the cemetery a mile away, and his grave is appropriately austere and simple: Philip Larkin 1922–1985 Writer is all it says. Somone has left a plain steel ballpoint pen at the foot of the headstone.

Yes, he was only 63: gulp again, almost the same age as me. Carpe diem again: back to the Duke of Cumberland (yet another of his favourite drinking haunts) for a final pint and toast to the man and his great works.

Which beer to have? Aha, the Wainwright: named after the walking-guide author Alfred. A self-contained, one-off man of words with a unique way of seeing the world. And occasionally a curmudgeonly old git. Yup, that’ll do nicely.

I very, very much enjoyed doing the Larkin Trail. Cheers!

Music for guitar: Pearson Park

Listen to my piece for classical guitar, written in 2022. It was inspired by the memories of this day’s ride. (MP3, 7min 20sec).