In 1984, Yorkshire had 56 coal mines. By 2015 that figure was zero. Little is left of the industry that defined much of the county’s community life and character, except for one vibrant, enduring legacy: a loathing of Margaret Thatcher and her government. But Barnsley can point to another legacy: Barnsley Main. The old entrance to the town’s mine and its stark winding gear are still there, Grade II-listed, and a very rare monument to the old way of life.

It’s easily visited by bike, only a mile or two from Barnsley’s rail station. I got there by taking some of the Trans Pennine Trail, newly tarmacked and offering easy mugging and getaway opportunities to the sinister, balaclavaed youth illegally riding the path on quad bikes and hacked e-bikes. I didn’t like the way they were sizing me up, wondering if this scruffy old bloke on a terrible bike would be worth doing over, and I took off on a narrow unquaddable bridleway before they could come to a decision.

The old mine building used to be part of a thriving complex, but now stands alone with just the graffiti, information boards, and occasional visitor for company. I nosed around it and admired the gaunt skeleton of winding gear that used to lower miners to their sometimes lethal work: the 1866 explosion that killed over 350 was only one of several disasters here.

Reluctant to go back along the smooth but intimidating path I’d come on, I went instead along the Dearne Valley path back to town, past anglers whose only threat to cyclists would have been an extraordinarily careless cast.

Central Barnsley doesn’t have a lot to write home about, not that there’d be any point because even first-class mail takes three days to arrive now. The town hall is a grand affair that George Orwell hated; in Road to Wigan Pier, he thought it was a waste of money that should have been spent on relieving poverty.

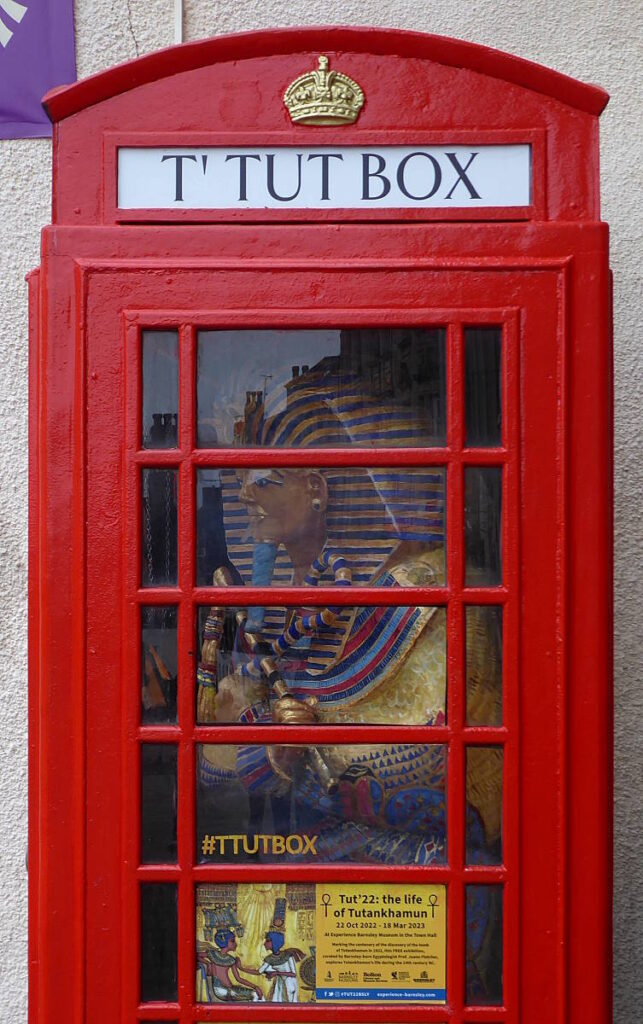

Facing it are two phone booths, repurposed not as libraries or defibrillator cabins, but one as a poetry board (words by Simon Armitage) and another a den for Tutankhamun. Perhaps he’s phoning home after some dreadful satnav misunderstanding to let Ankhesenamun know he’ll be late for tea after taking a wrong turn outside Thebes.

There’s also, just round the corner from it, a rather fetching old art-deco hotel facade that used to house a motor garage, and now plays host to a collection of wheelie bins.

The covered market had some good stalls, with unexotic but inviting ranges of food; the outdoor stalls in the pedestrian areas outside were more along the conventional shoes/ clothes/ confectionery line, though a jigsaw puzzle stall hinted at something a bit more off-piste – as did the kilted bagpiping busker, a bit incongruous in this West Yorkshire town.

The piazza has a statue of Barnsley’s most famous mythical son: the downtrodden Billy Casper of Barry Hines’s Kes, subject of a 1969 Ken Loach film. He squats here with his kestrel, nervous and edgy, as if expecting an attack by youths on quad bikes at any moment.

I would have liked to while an hour away at the Cooper Gallery’s promising arts hub, but there was no bike parking at all. When I asked the staff they looked bewildered, like I’d demanded somewhere to land my helicopter. So I gave that a miss.

I did find amusement at the Dickie Bird statue, though. I’m a great fan of sculptor Graham Ibbeson’s work – lively, approachable portraits of popular celebs doing what they were famous for. Eric Morecambe in Morecambe is the best-known example, and I’ve ridden to it several times; I’ve also biked past his Laurel & Hardy in Ulverston, and Fred Trueman in Skipton.

Dickie, like Fred, made his name in cricket – as a fair, accurate and humorous umpire, respected and liked by both sides. Ibbeson’s piece has him in typical smiling pose, giving a batter out with raised index finger, perhaps stating categorically ‘Thaaat’s ooooouuuuut!’.

The statue used to be lower down, but that raised finger proved a convenient prop for passing jokers on which to hang various bawdy or comical items, such as a bra and… well, you can probably imagine. So it’s now six foot up on a plinth, beyond the reach of all but the most determined pranksters.

It was the end of my innings in Barnsley too. I got the train back to Leeds, where I waited out my connection back home with a swift visit to another cricket legend: Hedley Verity. Not a statue, but a Wetherspoon.