Just two maps left to bag today. But getting from Whitby to the first of them, at Saltburn, was not as easy as the Tile Maps suggest, with their promise of a railway threading a picturesque coastal route all the way. That was one of mass-killer Beeching’s many victims in the 1960s.

So I’d have to cycle it. I started from the harbour, at the whalebone monument, and followed a short section of the old line from Whitby West Cliff station that’s now a green grassy stripe through a housing estate.

Cycling from Whitby to Saltburn is an uphill struggle. Several, actually. Not just because it’s very hilly, but because here is where National Cycle Route 1 – which nominally goes all the way from Dover to Shetland – simply gives up. There’s a gap between Whitby and Staithes: about eleven miles of busy A road with no sensible alternative for cyclists, only five-sides-of-a-hexagon detours.

Still, I took the main road out of Whitby to Sandsend, and climbed the steep climb of Lythe Bank, with views far behind me to the hazy cliffs and headlands of the North Yorkshire coast. There was respite at the top, where I turned off right to the little-visited, remote hamlets of Goldsborough and Kettleness. The old railway line pops out of a long tunnel or two here, and you can join it as a permissive path just by the old station, now a private house.

For two or three miles the old railway is a lovely, fair-surface track with some majestic clifftop views over Runswick Bay, a kind of smaller, ignored sibling of Robin Hood’s Bay. Those who were small, ignored siblings will understand its sense of injustice.

I got back to tarmac lanes at Runswick Bay and rejoined the main road to Staithes. This is another of North Yorkshire’s fishing villages that feels more like Devon or Cornwall, with little curved cobbled lanes, rough-and-ready cottages, a harbour full of lobster pots, pubs whose historic customer base was smugglers, and even an artistic community.

It also has what is possibly Britain’s narrowest alley. Dog Loup, just round the corner from the Cod & Lobster pub, is 15½ inches (39cm) wide at its narrowest point.

That’s narrower than the celebrated Parliament Street in Exeter (a capacious 25in, 64cm), narrower than the even more celebrated Temple Bar in Port Isaac, Cornwall (a comfortable 18 inches, 46cm). Far too narrow for bike handlebars, and rather narrower than my shoulders.

It even proved too narrow for a spaniel that briefly considered entering, but then desisted, perhaps judging that there was not enough space to cock a leg, so a waste of time.

I checked Dog Loup’s width to be absolutely sure. Being a cycle campaigner, I always carry a tape measure in my panniers, to determine the width of bike lanes, for instance. Obviously I only need a very short one.

Getting up and out of Staithes involves an abrupt clamber up Cowbar Bank, then a long and equally vertiginous ascent to the locality of Boulby. The cliffs here are the highest in Yorkshire and among the highest in Britain, at a diabolical 666 feet, or less diabolical 203m.

At the farm on the crest of the hill, I cycled past a concrete block that looked familiar. I’d seen similar on the Holderness coast, down in East Yorkshire, at Kilnsea. It was a World War I sound mirror: a kind of acoustic lens to pick up and focus the sound of distant planes to give a keen listener early warning of an attack.

It was a genius idea with two drawbacks. First, it required someone to sit there all day and all night with their ears cocked. Second, it didn’t work. Nevertheless, several were deployed round the east and south coasts. Only a handful survive today.

I sped through Loftus, ducked under a surviving bit of the Whitby–Saltburn railway line that only services a mine, and rolled through Brotton to arrive at Saltburn’s bracing seaside and pier. To get up from the beach level to the clifftop level station, I could have taken the funicular (£1.60, bikes welcome) but decided to cycle one last uphill instead.

Tile Map 8/9: Saltburn

Saltburn station is a terminus with a definite end-of-line feel, and no services or ticket offices, just a machine. But it has an original Tile Map in good condition, on the wall round the back, by the entrance to Sainsbury’s.

The supermarket had two bouncers on the door, which I didn’t know what to make of, but they were friendly and looked after my bike while I nipped in to buy a bottle of beer for my train journey past endless factories and defunct steelworks to the final Yorkshire Tile Map, at…

Tile Map 9/9: Middlesbrough

Journey’s End. You can tell Middlesbrough is a tough station because they play classical music on the platforms, because baroque sonata form to hoodlums and vandals is apparently like those high-pitched beeper things are to cats who you want to stop pooing in your garden.

So, the loudspeakers were full of a tinny rendition of the second movement of Haydn’s Symphony No 94 in G major. Which was a surprise.

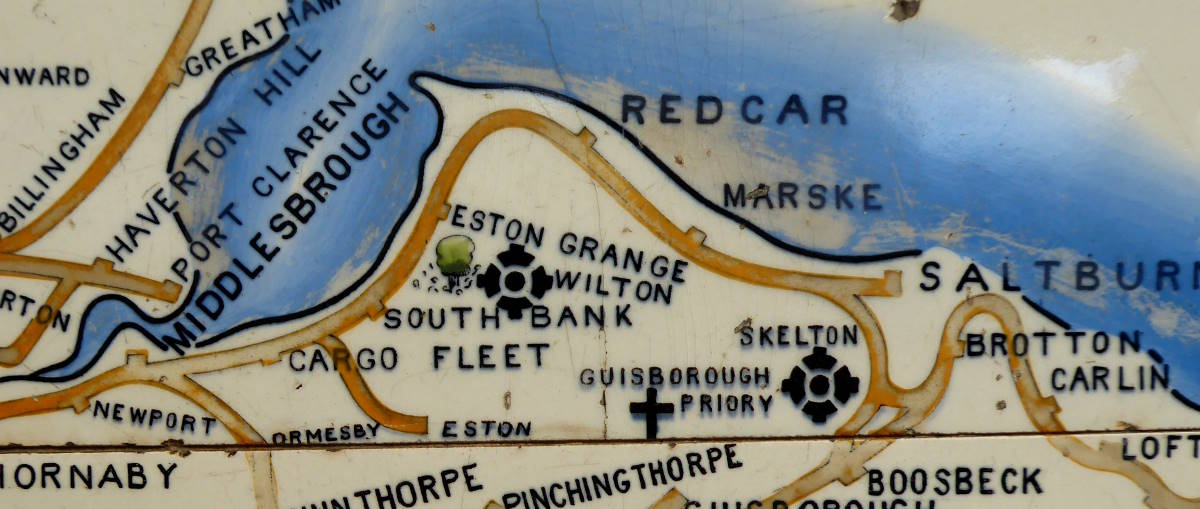

Middlesbrough’s Tile Map, proudly adorning a wall on Platform 2, is another fine example of the genre. I admired it over a bacon stottie the size of a bicycle wheel and enjoyed the feeling of a tick-box list completed. I decided against a visit to Middlesbrough’s iconic sight, the Transporter Bridge – I’ve been many times before, and sadly it’s been closed for years, waiting for a refurbishment that may never come. So from here it was an easy train ride back to York, where I began the trail earlier this week.

It’s been another super trip. I’ll be writing a magazine article or two about the Tile Maps Trail, maybe even getting a video together about it when I get a few days of free time. Which could be around 2027.

Meanwhile I hope I can put North Eastern Railways’ lovely piece of cartographic, ceramic and transport history on the Yorkshire visitor map. I think it deserves to be there. Tiles? Forget the ones that make up Google Maps. Go and see these.