East, West, Yorkshire’s best. We have everything here, including the very first bit of the Greenwich Prime Meridian: zero longitude, the dividing line between East and West. It makes its first landfall after the North Pole at a caravan park in Tunstall, on the windy Holderness coast. Just a few miles of flat farmland later, it leaves the great county and continues its beeline over the muddy Humber to Cleethorpes and the world beyond.

And, today, I rode it – well, as close as you can get, which meant a lot of wiggling on country lanes. You can see a map of the route at the bottom of this page.

Of course, there’s nothing geological or ‘natural’ about the Meridian. There’s no physical meaning to it, nothing visible on the ground or in the air. It’s a conceit, a device, a notional line for global clocks to zero on.

And a political bargaining chip. In 1884, Britain managed to bulldoze the world into taking Greenwich as their reference, because we were a major power respected internationally.

Not now, obviously. For a taste of those old heady days you’d have to go back to, oh, maybe 22 June 2016.

Anyway, a long-distance walking route follows the Meridian from Yorkshire all the way down to the south coast, and indeed people have cycled it (or as near as possible).

As well as the much-touristed monument in Greenwich itself, there are dozens, perhaps hundreds, of markers showing the line’s course down Britain (such as one in Cleethorpes). Well, Yorkshire has three of them, formerly four, and I visited them all today.

After starting out dodging polar bears in the frozen wastes of the North Pole, the zero line washes up on East Yorkshire’s coast at a caravan park. Sand le Mere is named after a lake that used to be here, and its accompanying village. Both were lost centuries ago to the North Sea, which erodes the coastline here faster than anywhere else in Europe.

Yorkshire is famous for having more acres (3,883,979 in 1901, when it was at full historical extent) than letters in the Bible (3,116,480 in the King James version). Is the title in danger? No. Even at present erosion rates, losing about 18.5 acres a year, we have another 415 centuries or so until parity.

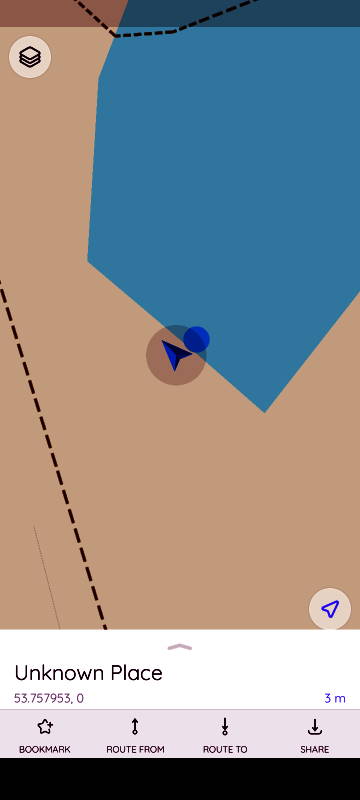

There used to be a monument on the beach showing the position of the Meridian, but it, too, has been gobbled up by the waves. (The caravan park is steadily losing pitches, too. That sea view gets steadily closer.) There’s only a scattering of rubble now. I wandered around until my phone’s map app displayed 0 as the longitude. This was the start of the Yorkshire Greenwich Meridian Trial.

Sand le Mere caravan park itself contains a quirky piece of architectural history. It’s a rare surviving example of the K4, a short-lived 1930s experiment that combined phonebox with postbox.

I remember visiting it in the 1980s. Then it was a few hundred yards further east, along a lane, by a car park – all now gone, claimed by the sea. The K4, being a listed structure, was moved inland to safety in the early 2000s.

None of it is operational now, just in case you were thinking of posting something and calling the recipients to alert them at the same time.

I headed south, roughly following the Meridian, having to divert through the seaside resort of Withernsea. There are two roadside markers for the line, the first on the B1362 just east of Church Lane, and the second on the B1445 just outside Patrington.

The signs are identical, apart maybe from the graffiti, though the southern one of the two has a shiny plaque with a map. So shiny I couldn’t actually read it.

This is an austere land of flat farmland, big skies, and wind turbines. Empty lanes run south to Patrington Haven and Sunk Island (which is neither an island, nor sunk). Outstray Road’s lonely tarmac alongside a drain gives out to a gravel lane, which then becomes a grassy track running west alongside the Humber. Its influence on British landscape art is well-known – everyone knows it’s none at all.

This scenery ain’t no oil painting, but there is something sparsely thrilling and elemental about all the waves, wind, water, wetlands and waders. There may not be much wow factor, but there are plenty of other Ws.

I plodded along to the Meridian Marker. To my left, a thin blue-grey line on the watery horizon: Spurn Point, visibly now cut off from the mainland, an island in the making. The shimmering steely waters of the Humber, plied with shipping. The dramatic tower of Grimsby Docks, a bizarre piece of Italianate architecture in Lincolnshire.

And there, in front of me, the concrete monument showing where the zero line leaves Yorkshire and heads to Greenwich, then France, Spain, Algeria, Mali, Burkina Faso, Togo, Ghana and ultimately Antarctica.

I couldn’t resist one more piece of quirkery. A few miles away in Kilnsea, the gateway village for Spurn Point, is a World War I Sound Mirror. Several of these giant concrete dishes were constructed round Britain’s south and east coasts, the idea being that they focused the exact frequency of German zeppelins on to a microphone, which could detect the invaders early.

There was one problem. They didn’t work, and they were quickly abandoned in favour of the exciting new science of radar. A handful of sound mirrors remain, including this one in a farmer’s field, looking like an upended giant’s ashtray. A footpath from the adjacent nature reserve, past a couple of bird hides, gives a good view.

I listened carefully. All I could hear was wind, waves and water. I was happy. But it was time to leave the mystic east behind, and return to the logical, rational west.