British railtrails are typically smooth, wide tarmac. For two miles. Then gravel. Then muddy path. Then a fenced bridleway round a cement factory, then a path through a housing estate, then a shared-use track alongside an A road.

Well, not in Belgium. Their RAVeL network, much of it on old railway lines, is generally excellent: bicycle roads, free of traffic, almost all level.

And perhaps excellentest of the lot is the Vennbahn. It runs 80-odd miles south from Aachen, near the Dutch–German–Belgian tripoint, down to Troisvierges in the far north of Luxembourg, though that’s not particularly distant from the far south of Luxembourg.

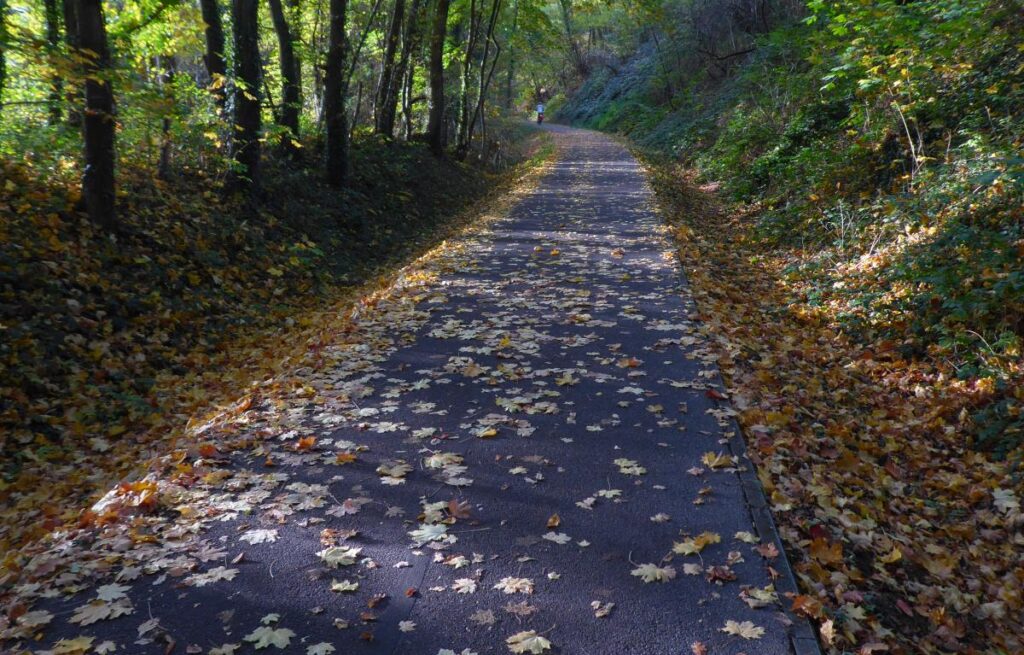

And the top sixty miles of the Vennbahn, from Aachen to just past St Vith (that Belgian curio, a German-speaking town), are superb, not just skating-smooth surfaces, but winding through pleasant, woody landscapes.

There’s a twist, too. For complicated historical reasons – aren’t they always, in Europe – the track is part of Belgium, even for the stretches of a few miles here and there where it goes spaghetti-like through Germany. (The Tim Traveller’s YouTube channel has an entertaining video explaining all.) Cars crossing over it, at the odd road bridge, duck into a foreign country for a faction of a second. If ever the countries adopt conflicting road-pricing models, there could be some fine detail to iron out.

But I don’t care about the cars. I care about the cycling. And the Vennbahn is wonderful, a candidate for Europe’s most enjoyable railtrail, perhaps most enjoyable car-free bike path of any kind.

Anyway, I set off from Aachen to join the start of the Vennbahn accompanied briefly by Nigel – my companion on the recent Austria End to End – before he struck north to catch his ferry home. It was a glorious day, sunny and warm despite being almost November. The shops back in England were desperately flogging Christmas already, and here was I in a T-shirt and shorts.

There’s no signage clues to those slivers of Belgium that cut through Germany. I had to keep an eye on my phone’s maps.me app to ascertain if those trees on either side would prefer chips swamped in mayo washed down by a dubbel, or if they’d go for Kartoffelsalat and a pils.

I passed Monschau, a historic half-timbered town, and couldn’t resist riding down to it. Last time I came here, in 1999, it was flooded, and we watched the water levels anxiously from inside our sodden tent.

No such problems this time: the only flood was that of tourists. I picnicked in the main square, snapped industriously, and felt very happy.

After the modest climb back up to rejoin the Vennbahn, I was delighted to see a kiosk selling cold beers, and continued my way blissfully with a small local brew inside me.

The ‘Venn’ of the route’s title is the word for ‘fen’, and long stretches after Monschau are indeed fenny, though with more tussocky greenery on them, and more altitude underneath them, than the drained flatlands of say Cambridgeshire. Lovely day, lovely cycling.

After Waimes I was following the section of the Vennbahn I did on my Belgium End to End earlier this year, and stayed in the same hostel at St Vith, busy with families now as then. And, I rather fancy, had the same beers for my post-ride wind-down.

It’s 55 or so miles from Aachen to St Vith; I doubt there are fifty-five easier or more enjoyable miles on the continent to ride. But then I’m a fan of informed scepticism.